Sir George Grey was eager to set up a learning institute for Māori to educate and to teach them technical and industrial skills. Under instruction from Sir George Grey, Donald McLean approached Wairarapa Māori leaders asking them to set aside two pieces of land for the purpose of building a school for their children.

The proposal was to set up two schools, one at Kaikōkirikiri for girls to learn to read and write and learn numeracy but also to learn homemaking skills and domestic duties. A farm was also proposed to grow crops and wheat to help support the school and also proposed was a flour mill to train Māori how to produce flour for use and sale.

The exact same scheme was also proposed for Papawai for boys to learn carpentry and farming along with reading and writing and numeracy.

Education during this time was largely a missionary enterprise with State funding being provided under the 1847 Education Ordinance.

Kaikōkirikiri:

Kaikōkirikiri was a very large fortified Pā on the banks of the Waipoua River. The principal chief was Te Retimana Te Korou.

About 1853, 190 acres at Kaikokirikiri was gifted to Bishop Selwyn. Kaikokirikiri was part of the larger Kuhangawariwari block and was later referred to as the Bishops Reserve.

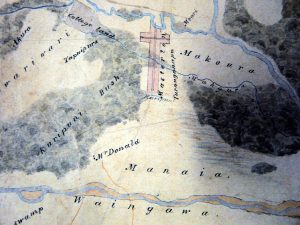

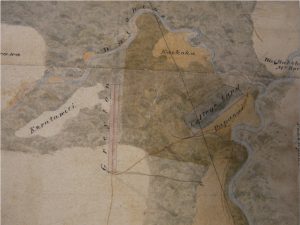

Two years later in 1855 surveyors had drawn in the College lands, which showed heavy bush growth and 10 years later in 1865 an updated sketch map was produced showing the College lands on the outskirts of the Masterton Township.

In 1879, 15½ acres was taken under the Public Works Act for rail and road purposes.

During the construction of the church, the Pākeha builder died by his own hand and as a result of the tapu placed on the building, Māori stayed away. With the absence of Māori support, further construction was halted.

The gifting of land known as “tukuwhēnua” was the lands were held in “trust to be returned when no longer required for the intended purpose”. Prominent Māori leaders insisted the land be returned to the rightful owners.

Through all the turmoil, the proposed school at Kaikōkirikiri was not built.

Papawai:

Papawai and the greater surrounding area was heavily covered in native bush. A track from Greytown (Hupenui) cut through the bush to Papawai, a distance of about 2 miles that early travellers either made on foot or on horseback.

Sir George Grey accompanied by Bishop Selwyn discussed with the principal leaders Te Manihera Rangi-taka-i-waho, Pirika Te Po, Te Warahi and Te Watarauhihi how a school at Papawai would prepare their children for trade and industry jobs and provide them with the necessary skills to manage and to farm their own land holdings.

As proposed, it was to be a boarding school for boys and along with the school, a church was promised and a flour mill to be built to help sustain the school and an expected growth in population.

In 1853 the principal leaders of Papawai gifted 400 acres.

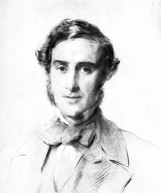

Rev. William Ronaldson was appointed as the resident missionary for Papawai. He was born in 1823, the son of a London wine merchant and served his early days on board a whaling ship. He arrived in NZ about 1855.

He lived in Greytown with his family and walked the 2 miles every day to and from Papawai. During good weather, the journey would take him about an hour and when it rained the track would turn to mud and his journey would take him longer.

With a grant of £500 tradesmen were employed to prepare timber for the construction of a parsonage for the Rev and his family.

The land for the school was gifted in 1853 yet it took the Government subsidised church seven years to build the school. In 1858, Rev. William Ronaldson moved into his new residence and oversaw the completion of the school house which housed the upstairs dormitory and the cook house sited nearby.

On December 21, 1860 the first Māori school in the Wairarapa was opened at Papawai by the Anglican Bishop of Wellington, C.J. Abraham and in honour of the day was named Hato Tāmati (Saint Thomas) with an opening student roll of 16 pupils. A number of Pākeha settlers also enrolled their children at the school.

The Parsonage with the school behind and the cookhouse and dining room on the side. Upstairs in the school house was the student dormitory.

The opening of Hato Tāmati (St Thomas) was a proud moment and was gladly welcomed by the wider community but the annual subsidy of £10 per pupil wasn’t enough to feed and to clothe the students let alone pay wages for a teacher.

Ronaldson regularly journeyed to Wellington to ask the Church and the State for more financial aid but his pleas fell on deaf ears.

Adding to the problem was the expected population growth didn’t happen and there was arguments over the ownership of the flour mill that sat idle. Fundraising efforts by the local community wasn’t enough and with miserly support from both the Church and the State, Ronaldson had no choice but to close the school.

It took 7 years to build the school and 4 years later, January 1865, Hato Tāmati – the College of Saint Thomas closed its doors for the last time.

Rev. William Ronaldson passed away in Dunedin 1917.

Hikurangi:

The Tancred Estate was located in Clareville and was owned by Sir Thomas and Lady Jane Tancred (Prideaux). Sir Thomas passed away 1880 and Lady Tancred passed away in 1901. The Estate was purchased by the Anglican Church and leased to Papawai and Kaikōkirikiri Trust and became known as Hikurangi Anglican Māori Boys College. The school roll also included a large number of Pākeha students.

The College opened in 1903 and was named Hikurangi by Papawai paramount chief Hamuera Tamahau Mahupuku. Hamuera attended Hato Tāmati – St Thomas at Papawai and stated that Hikurangi was born out of Hato Tāmati and the irony is that Rev. William Ronaldson came out of retirement to help with the school’s opening ceremony November 1903.

The two storey home accommodated the house master and his family, staff and students as well as class rooms. With a growing school roll and heavy demands on limited services, Hikurangi was in need of larger amenities.

In 1907 Hikurangi underwent a huge transformation. An added extension provided student accommodation, dining and laundry rooms and a principal’s accommodation. Behind was a woodwork room, a swimming pool and each student had their own vegetable garden.

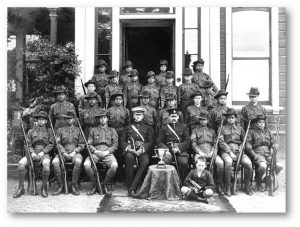

The school syllabus was very advanced for its time. In addition to normal subjects (sports), also included was music, French, technical drawing and school army cadets.

Religious studies was an important part of life at Hikurangi – pupils attended the chapel twice daily and more often on important occasions like Christmas and Easter.

March 1932 around lunch time, fire broke out in the school kitchen. Staff and pupils evacuated the building with everyone making a grand effort to save what they could. A stiff breeze fanned the fire and within an hour and a half, the old two storey wooden building was completely reduced to ashes.

School records, personal property, archival records, library books all school material and resources were lost. March 1932 signalled the end of Hikurangi College. The chapel, constructed out of brick and mortar was the only building to escape the fire and stood alone at Hikurangi for another 10 years.

Early evening, June 1942 Wairarapa was hit with a strong earthquake and later that same evening another severe jolt rocked the Wairarapa. Brick buildings throughout the lower North Island suffered irreparable damage and the last remaining building at Hikurangi suffered the same fate and brought to an end Hikurangi – it was the end of an era.